EARLY XINJIANG HISTORY

Xinjiang is as much part of Central Asia as it is of China. Central Asia has a rich history with more than its share of conquests and invasions. It was lively commercial center that lay at the axis of the Silk Road trade between Asia and Europe. It was also a major a center of education, art, architecture, religion, poetry and science.

Xinjiang is as much part of Central Asia as it is of China. Central Asia has a rich history with more than its share of conquests and invasions. It was lively commercial center that lay at the axis of the Silk Road trade between Asia and Europe. It was also a major a center of education, art, architecture, religion, poetry and science. The first settlers, the Tocharians, were herders who spoke an Indo-European language and appear to have worshiped cows. Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times, “I say the Tarim Basin was one of the last parts of the earth to be occupied. It was bound by mountains. They couldn’t live there until they had certain irrigation technologies.”

The first settlers, the Tocharians, were herders who spoke an Indo-European language and appear to have worshiped cows. Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times, “I say the Tarim Basin was one of the last parts of the earth to be occupied. It was bound by mountains. They couldn’t live there until they had certain irrigation technologies.” The British historian Arnold Toynbee described Central Asia as a "roundabout" where routes covered "from all quarters of the compass and from which routes radiate out to all quarters of the compass again." Influence ove the region has come from Siberia, Mongolia, China, Persia, Turkey and Russia.

The British historian Arnold Toynbee described Central Asia as a "roundabout" where routes covered "from all quarters of the compass and from which routes radiate out to all quarters of the compass again." Influence ove the region has come from Siberia, Mongolia, China, Persia, Turkey and Russia. Crossroads of history has been used to describe a lot of places but nowhere is it more apt than in Central Asia. So many groups—a lot of the with names Westerners are unfamiliar with—came, inhabited, passed through, settled, conquered, left and stayed, and it is hard to keep track of them all. They came from all directions, and represented many different religions and ethnic groups from both Europe and Asia.

Crossroads of history has been used to describe a lot of places but nowhere is it more apt than in Central Asia. So many groups—a lot of the with names Westerners are unfamiliar with—came, inhabited, passed through, settled, conquered, left and stayed, and it is hard to keep track of them all. They came from all directions, and represented many different religions and ethnic groups from both Europe and Asia.Websites and Resources

2nd century A.D.cup

found in Xinjiang with

Greco-Roman gladiator

Good Websites and Sources: Muslimwiki Islam in China Muslimwiki Islam in China ;Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Blog with stuff on Xinjiang china.notspecial.org ; About Xinjiang (Chinese government site) aboutxinjiang. ; History and Development of Xinjiang (Chinese government site) news.xinhuanet.com ; Uighurs and XinjiangCouncil on Foreign Relations ; Muslims in China: Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awarenessislamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Asia Times atimes.com ; Xinjiang History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Great Game Info sras.org ; Great Game in Afghanistan atimes.com ; Separatism and Human Rights: Wikipedia article on Terrorism in China Wikipedia ;All Quiet on the Western Front? silkroadstudies.org Human Rights in Xinjiang Human Rights Watch article hrw.org ; Human Rights in Xinjiang Human Rights Watch article hrw.org ; Human Rights in Xinjiang Human Rights Watch article hrw.org ; Uighur and Xinjiang Experts: Dru Gladney of Pomona College; Nicolas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch; and James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown University. Book: Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang by James A Millward (C Hurst, 2007).

Good Websites and Sources: Muslimwiki Islam in China Muslimwiki Islam in China ;Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Blog with stuff on Xinjiang china.notspecial.org ; About Xinjiang (Chinese government site) aboutxinjiang. ; History and Development of Xinjiang (Chinese government site) news.xinhuanet.com ; Uighurs and XinjiangCouncil on Foreign Relations ; Muslims in China: Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awarenessislamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Asia Times atimes.com ; Xinjiang History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Great Game Info sras.org ; Great Game in Afghanistan atimes.com ; Separatism and Human Rights: Wikipedia article on Terrorism in China Wikipedia ;All Quiet on the Western Front? silkroadstudies.org Human Rights in Xinjiang Human Rights Watch article hrw.org ; Human Rights in Xinjiang Human Rights Watch article hrw.org ; Human Rights in Xinjiang Human Rights Watch article hrw.org ; Uighur and Xinjiang Experts: Dru Gladney of Pomona College; Nicolas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch; and James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown University. Book: Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang by James A Millward (C Hurst, 2007). Links in this Website: XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORYFactsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG AND CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG SEPARATISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; TERRORISM IN XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG RIOTS IN 2009 Factsanddetails.com/China ; UIGHURS Factsanddetails.com/China ; HORSEMEN AND SMALL MINORITIES IN XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG, URUMQI Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG. KASHGARFactsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG KARAKORUM HIGHWAY Factsanddetails.com/China

Links in this Website: XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORYFactsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG AND CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG SEPARATISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; TERRORISM IN XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG RIOTS IN 2009 Factsanddetails.com/China ; UIGHURS Factsanddetails.com/China ; HORSEMEN AND SMALL MINORITIES IN XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG, URUMQI Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG. KASHGARFactsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG KARAKORUM HIGHWAY Factsanddetails.com/China

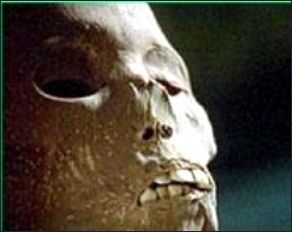

Tarim mummy

PLACES IN XINJIANG : Xinjiang Tourism Administration, 16 South Hetan Rd, 830002 Urumqi, Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 991-282-7912, fax: (0)- 991-282-4449. Web Sites : Wikipedia Wikipedia Government site Xinjiang.gov ; Photos and Qanats : SynapticSynaptic Wikipedia article on qanats Wikipedia ; Turpan : Turpan Tourism Division, 41 Qingnian Rd, 838000 Turpan. Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 995-523-706, fax: (0)- 995-522-768 ; Urumqi : Urumqi Tourism Bureau, 32 Guangming Rd, 830002 Urumqi, Xinjiang China, tel. (0)-991-283-2212, fax: (0)- 991-281-9357 Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; China Map Guide China Map Guide ; Getting There Sites : Urumqi is accessible by air and bus and lies at the end on the main east-west train line from Beijing. It is connected to Kashgar and other Xinjiang cities to southwest by a new train that began operating in the early 2000s.Travel China Guide (click transportation) Travel China Guide Tian Shan : WikipediaWikipedia ; Links in this Website: XINJIANG, URUMQI Factsanddetails.com/China

PLACES IN XINJIANG : Xinjiang Tourism Administration, 16 South Hetan Rd, 830002 Urumqi, Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 991-282-7912, fax: (0)- 991-282-4449. Web Sites : Wikipedia Wikipedia Government site Xinjiang.gov ; Photos and Qanats : SynapticSynaptic Wikipedia article on qanats Wikipedia ; Turpan : Turpan Tourism Division, 41 Qingnian Rd, 838000 Turpan. Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 995-523-706, fax: (0)- 995-522-768 ; Urumqi : Urumqi Tourism Bureau, 32 Guangming Rd, 830002 Urumqi, Xinjiang China, tel. (0)-991-283-2212, fax: (0)- 991-281-9357 Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; China Map Guide China Map Guide ; Getting There Sites : Urumqi is accessible by air and bus and lies at the end on the main east-west train line from Beijing. It is connected to Kashgar and other Xinjiang cities to southwest by a new train that began operating in the early 2000s.Travel China Guide (click transportation) Travel China Guide Tian Shan : WikipediaWikipedia ; Links in this Website: XINJIANG, URUMQI Factsanddetails.com/China Kashgar Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; Lonely Planet Lonely Planet ; China Vista China Vista ; Getting There: Kashgar is accessible by air and bus and connected to Urumqi and the rest of China by a new train that began operating in 2004. There are two daily trains between Kasghar and Urumqi that cover the 1,598 kilometer distance in about 24 hours, There are also flights on Xinjiang Airlines 757s every evening. Website:CNINFO.net Travel China Guide (click transportation) Travel China Guide Lonely Planet (click Getting There) Lonely Planet ; Links in this Website:XINJIANG. KASHGAR Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG KARAKORUM HIGHWAY Factsanddetails.com/China

Kashgar Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; Lonely Planet Lonely Planet ; China Vista China Vista ; Getting There: Kashgar is accessible by air and bus and connected to Urumqi and the rest of China by a new train that began operating in 2004. There are two daily trains between Kasghar and Urumqi that cover the 1,598 kilometer distance in about 24 hours, There are also flights on Xinjiang Airlines 757s every evening. Website:CNINFO.net Travel China Guide (click transportation) Travel China Guide Lonely Planet (click Getting There) Lonely Planet ; Links in this Website:XINJIANG. KASHGAR Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG KARAKORUM HIGHWAY Factsanddetails.com/ChinaTarim Mummies in Xinjiang (Western China)

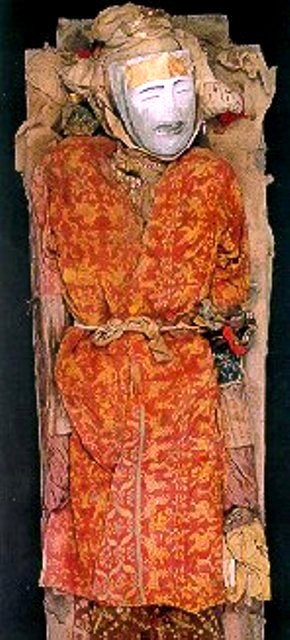

Cherchen Ma, Tarim mummy

Hundreds of mummies hundreds and thousands of years old have been discovered in Xinjiang. They span a period of time from 1800 BC to as recently as the Ching dynasty (1644-1912) and come from all walks of life. Some were kings and warriors, others housewives and farmers. "They were ordinary people who lived and died in Xinjiang over the ages,'' Wang Binghua, a retired archaeologist who exhumed many of the mummies, told the Los Angeles Times. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

Hundreds of mummies hundreds and thousands of years old have been discovered in Xinjiang. They span a period of time from 1800 BC to as recently as the Ching dynasty (1644-1912) and come from all walks of life. Some were kings and warriors, others housewives and farmers. "They were ordinary people who lived and died in Xinjiang over the ages,'' Wang Binghua, a retired archaeologist who exhumed many of the mummies, told the Los Angeles Times. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010] Most of the mummies have been found in a vast area in the Taklimakan desert known as the Tarim Basin. Once crossed by rivers and freckled with oases and settlements, the basin was located at a crossroads between Europe and Asia and was home at different times to an astonishing mix of peoples — Europeans, Siberians, Mongolians, Han Chinese. Today the terrain is so dry and wind-swept it is almost uninhabitable, [Ibid]

Most of the mummies have been found in a vast area in the Taklimakan desert known as the Tarim Basin. Once crossed by rivers and freckled with oases and settlements, the basin was located at a crossroads between Europe and Asia and was home at different times to an astonishing mix of peoples — Europeans, Siberians, Mongolians, Han Chinese. Today the terrain is so dry and wind-swept it is almost uninhabitable, [Ibid] The Tarim mummies are among the greatest recent archaeological finds in China, perhaps the world. Four are in glass display cases in the main museum in Urumqi. Their skin is parched and blackened from the wear and tear of thousands of years, but their bodies are strikingly intact. The arid conditions in the desert and the salty sand found in this region have kept the mummies in amazingly good condition. Unlike the embalmed mummies of ancient Egypt, they were preserved naturally by the elements. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008]

The Tarim mummies are among the greatest recent archaeological finds in China, perhaps the world. Four are in glass display cases in the main museum in Urumqi. Their skin is parched and blackened from the wear and tear of thousands of years, but their bodies are strikingly intact. The arid conditions in the desert and the salty sand found in this region have kept the mummies in amazingly good condition. Unlike the embalmed mummies of ancient Egypt, they were preserved naturally by the elements. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008] Book: The Mummies of Urumchi by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (W.W. Norton, 1999)

Book: The Mummies of Urumchi by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (W.W. Norton, 1999)History of the Tarim Mummies

Tarim mummy

Mummies have been found at several sites in the Tarim basin and western China. Archaeologists have unearthed the mummified remains of about a hundred individuals at the Niya site, not far from Lop Nur. Many mummies have also been found in the arid salt beds near Urumqi.

Mummies have been found at several sites in the Tarim basin and western China. Archaeologists have unearthed the mummified remains of about a hundred individuals at the Niya site, not far from Lop Nur. Many mummies have also been found in the arid salt beds near Urumqi. Several famous ones have been found in Loulan, an oasis town on the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, where the northern and southern branches of the Silk Road came together, and near the Lop Nur nuclear testing site. The kingdom of Loulan thrived for 700 years beginning in the 2nd century B.C. Many discoveries came from the Xiaohe tombs there. The Xiaohe Tombs were discovered in 1934 by a Swedish explorer and excavated by a Chinese team starting in 2000. They have been dated as being between 3,000 and 4,000 years old, making them between 2,000 and 1,000 years older than the Loulan Kingdom.

Several famous ones have been found in Loulan, an oasis town on the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, where the northern and southern branches of the Silk Road came together, and near the Lop Nur nuclear testing site. The kingdom of Loulan thrived for 700 years beginning in the 2nd century B.C. Many discoveries came from the Xiaohe tombs there. The Xiaohe Tombs were discovered in 1934 by a Swedish explorer and excavated by a Chinese team starting in 2000. They have been dated as being between 3,000 and 4,000 years old, making them between 2,000 and 1,000 years older than the Loulan Kingdom. Yidilisi Abuduresula is a Uighur archaeologist working at Xiaohe, where 350 graves have been discovered. The bottom layer of graves dates back nearly 4,000 years. More recent graves point to a matriarchal herding society that worshiped cows, Abuduresula said.

Yidilisi Abuduresula is a Uighur archaeologist working at Xiaohe, where 350 graves have been discovered. The bottom layer of graves dates back nearly 4,000 years. More recent graves point to a matriarchal herding society that worshiped cows, Abuduresula said. The oldest mummies, were probably Tocharians, herders who traveled eastward across the Central Asian steppes and whose language belonged to the Indo-European family. The mummies at the Niya site probably belonged to the Afanasievo or later Andronova cultures of the Russian steppes. A second wave of migrants came from what is now Iran.

The oldest mummies, were probably Tocharians, herders who traveled eastward across the Central Asian steppes and whose language belonged to the Indo-European family. The mummies at the Niya site probably belonged to the Afanasievo or later Andronova cultures of the Russian steppes. A second wave of migrants came from what is now Iran. Some may have come from as far away as Europe. A mummy from the Lop Nur area, the2,000-year-old Yingpan Man, was unearthed wearing a hemp death mask with gold foil and a red robe decorated with naked angelic figures and antelopes—all hallmarks of a Hellenistic civilization.

Some may have come from as far away as Europe. A mummy from the Lop Nur area, the2,000-year-old Yingpan Man, was unearthed wearing a hemp death mask with gold foil and a red robe decorated with naked angelic figures and antelopes—all hallmarks of a Hellenistic civilization.Individuals Among the Xinjiang Mummies

Tarim mummy

“All the mummies tell a story,” Demick wrote. “In an ancient graveyard in Astana, near Turpan, a man and a woman are buried together in an underground crypt that dates from the Tang dynasty (AD 618-906) and is one of the few places that the public can see mummies in their original graves. The woman looks younger than the man. Her mouth is in a grimace; forensic specialists say her arm and neck were broken shortly before her death.” "We think she might have been beaten and buried alive to be with her husband. He died naturally,'' said Bai Yingcai, a tour guide and mummy expert who was taking visitors through the crypts. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

“All the mummies tell a story,” Demick wrote. “In an ancient graveyard in Astana, near Turpan, a man and a woman are buried together in an underground crypt that dates from the Tang dynasty (AD 618-906) and is one of the few places that the public can see mummies in their original graves. The woman looks younger than the man. Her mouth is in a grimace; forensic specialists say her arm and neck were broken shortly before her death.” "We think she might have been beaten and buried alive to be with her husband. He died naturally,'' said Bai Yingcai, a tour guide and mummy expert who was taking visitors through the crypts. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010] One man who lived in the 3rd or 4th century AD who was 6 feet 6 and dressed in magnificent red and gold embroidered clothing A 3-month-old baby (8th century) with a felt bonnet and small blue stones covering the eyes, which were possibly the same color. Some of the men have red beards; the women have long blond braids.

One man who lived in the 3rd or 4th century AD who was 6 feet 6 and dressed in magnificent red and gold embroidered clothing A 3-month-old baby (8th century) with a felt bonnet and small blue stones covering the eyes, which were possibly the same color. Some of the men have red beards; the women have long blond braids. The body of a 55-year-old man dug up from a 3000-year old grave was dressed in woolen garments and deerskin boots very similar to those worn by horsemen who live in western China today. His hands were bound together with a red woolen bracelet and he was buried with three women and a horse's skull and leg hollowed and stuffed with reeds.

The body of a 55-year-old man dug up from a 3000-year old grave was dressed in woolen garments and deerskin boots very similar to those worn by horsemen who live in western China today. His hands were bound together with a red woolen bracelet and he was buried with three women and a horse's skull and leg hollowed and stuffed with reeds. A 50-centimeter-long mummy of an infant boy, found in the 1980s near Khotan in the Taklamakan desert, was wrapped in bag made from sheep skin placed inside a small coffin lined with white felt. Smooth stones were placed over each eye. The nostrils were stuffed with pieces` of vermillion yarn. The face is painted making him look like a doll. A tiny milk feeder made from the skin of a sheep teat was placed near his side.

A 50-centimeter-long mummy of an infant boy, found in the 1980s near Khotan in the Taklamakan desert, was wrapped in bag made from sheep skin placed inside a small coffin lined with white felt. Smooth stones were placed over each eye. The nostrils were stuffed with pieces` of vermillion yarn. The face is painted making him look like a doll. A tiny milk feeder made from the skin of a sheep teat was placed near his side. Other finds from the Xiaohe Tombs include: 1) a burial mask with teeth made of bird feathers and no eyes; 2) pointed hats like those seen in Persian carvings; and 3) a 135-centimeter wooden model of a mummy in a boat-shaped coffin that is though to represent a person who for some reason or another couldn’t be buried there but wanted to. Some of the carving also resemble Bronze Age carvings found in tombs on New Grange in Ireland.

Other finds from the Xiaohe Tombs include: 1) a burial mask with teeth made of bird feathers and no eyes; 2) pointed hats like those seen in Persian carvings; and 3) a 135-centimeter wooden model of a mummy in a boat-shaped coffin that is though to represent a person who for some reason or another couldn’t be buried there but wanted to. Some of the carving also resemble Bronze Age carvings found in tombs on New Grange in Ireland.Loulan Beauty

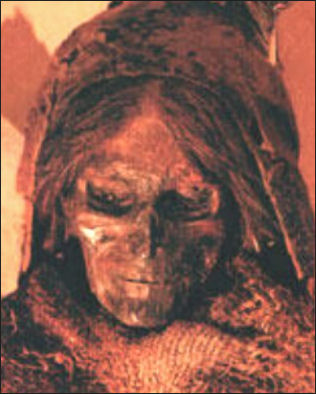

Loulan Beauty

The most famous mummy unearthed in the Taklimakan desert is that of woman with long reddish blonde hair. Discovered near Loulan in 1979 and nicknamed the "Loulan Beauty," she was five feet tall and was buried wearing a goatskin wrap, woolen cape, leather shoes and a hat trimmed with goose feathers. Carbon-dating indicates that her body is 3,800 years old but similar tests of the wood of the coffin of mummy found nearby remotely suggest that she could be 6,000 years old. She is also known as the Xiaohe Princess.

The most famous mummy unearthed in the Taklimakan desert is that of woman with long reddish blonde hair. Discovered near Loulan in 1979 and nicknamed the "Loulan Beauty," she was five feet tall and was buried wearing a goatskin wrap, woolen cape, leather shoes and a hat trimmed with goose feathers. Carbon-dating indicates that her body is 3,800 years old but similar tests of the wood of the coffin of mummy found nearby remotely suggest that she could be 6,000 years old. She is also known as the Xiaohe Princess. The Loulan Beauty was unearthed in 1980 by Chinese archaeologists who were working with a television crew on a film about the Silk Road near Lop Nur, a dried salt lake 120 miles from Urumqi that has been used by the Chinese for nuclear testing. Thanks to the extreme dryness and the preservative properties of salt, the corpse was remarkably intact — her eyelashes, the fine hair on her skin, even the lines on her skin were visible. She was buried face up about 3 feet under, wrapped in a simple woolen cloth and dressed in a goatskin, a felt hat and leather shoes. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

The Loulan Beauty was unearthed in 1980 by Chinese archaeologists who were working with a television crew on a film about the Silk Road near Lop Nur, a dried salt lake 120 miles from Urumqi that has been used by the Chinese for nuclear testing. Thanks to the extreme dryness and the preservative properties of salt, the corpse was remarkably intact — her eyelashes, the fine hair on her skin, even the lines on her skin were visible. She was buried face up about 3 feet under, wrapped in a simple woolen cloth and dressed in a goatskin, a felt hat and leather shoes. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010] Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “ What was most remarkable about the corpsewas that she appeared to be Caucasian, with her telltale large nose, narrow jaw and reddish-brown hair. The discovery turned on its head assumptions that Caucasians didn't frequent these parts until at least a thousand years later, when trading between Europe and Asia began along the Silk Road. Since Uighurs themselves often resemble Europeans rather than Chinese, many were quick to adopt the Beauty of Loulan as one of their own.” "If you went to see the mummy in the museum, a Uighur would come up to you and whisper proudly, 'She's our ancestor,'" said Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese studies at the University of Pennsylvania. "It became a political hot potato." [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “ What was most remarkable about the corpsewas that she appeared to be Caucasian, with her telltale large nose, narrow jaw and reddish-brown hair. The discovery turned on its head assumptions that Caucasians didn't frequent these parts until at least a thousand years later, when trading between Europe and Asia began along the Silk Road. Since Uighurs themselves often resemble Europeans rather than Chinese, many were quick to adopt the Beauty of Loulan as one of their own.” "If you went to see the mummy in the museum, a Uighur would come up to you and whisper proudly, 'She's our ancestor,'" said Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese studies at the University of Pennsylvania. "It became a political hot potato." [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010] Despite her fine features, lived a hardscrabble life. Her shoes and clothing had repeatedly been mended. Her hair was infested with lice. She had ingested a considerable amount of sand, dust and charcoal, and lung failure most likely caused her to die in her early 40s. "You can see that even back then, pollution was a problem," said Wang. [Ibid]

Despite her fine features, lived a hardscrabble life. Her shoes and clothing had repeatedly been mended. Her hair was infested with lice. She had ingested a considerable amount of sand, dust and charcoal, and lung failure most likely caused her to die in her early 40s. "You can see that even back then, pollution was a problem," said Wang. [Ibid]Lifestyle of Ancient People of Western China

The people who lived in western China 3,000 years ago were farmers and animal herders. They ate stewed mutton cooked over an open fire and round bread similar to what people in western China eat today. The early inhabitants of Niya lived in homes built of stones, mud bricks or reeds and posts, with fireplaces, stucco walls with floral designs.

The people who lived in western China 3,000 years ago were farmers and animal herders. They ate stewed mutton cooked over an open fire and round bread similar to what people in western China eat today. The early inhabitants of Niya lived in homes built of stones, mud bricks or reeds and posts, with fireplaces, stucco walls with floral designs. Excavated temples were painted with sun symbols that seem to indicate that they worshiped Mithra, an Indo-Iranian god. Wood carving and furniture had depictions of elephants and mythical beasts found in Greek and Roman art and the art of other cultures. Hundreds of wooden documents" were inscribed with Kharosshthi script, an Indian alphabet of Aramaic origin dating back to the fifth century B.C., and used to record Silk Road transactions. [Source: Thomas B. Allen, National Geographic, March 1996]

Excavated temples were painted with sun symbols that seem to indicate that they worshiped Mithra, an Indo-Iranian god. Wood carving and furniture had depictions of elephants and mythical beasts found in Greek and Roman art and the art of other cultures. Hundreds of wooden documents" were inscribed with Kharosshthi script, an Indian alphabet of Aramaic origin dating back to the fifth century B.C., and used to record Silk Road transactions. [Source: Thomas B. Allen, National Geographic, March 1996]Interesting Finds Among the Xinjiang Mummies

Often, the mummies' accessories are more interesting than the bodies themselves. Some have high pointed hats; another, possibly a healer, was buried with a bag of marijuana. Wang, the Chinese archaeologist, told the Los Angeles Times: "You can study the mummies to learn what these people ate, how they dressed, their social life, their standards of beauty, how they interacted with others. This information is very precious.''

Often, the mummies' accessories are more interesting than the bodies themselves. Some have high pointed hats; another, possibly a healer, was buried with a bag of marijuana. Wang, the Chinese archaeologist, told the Los Angeles Times: "You can study the mummies to learn what these people ate, how they dressed, their social life, their standards of beauty, how they interacted with others. This information is very precious.'' In one cemetery in Hami, in northeastern Xinjiang, archaeologists found plaid fabric similar to what you'd see on a Scottish kilt. Elizabeth Barber, a professor emeritus at Occidental College and a leading expert on ancient textiles, used the cloth to surmise that the mummies shared Celtic ancestry with the Scots. In fact, the cloth was almost the same as samples found in ancient salt mines in Hallstatt, Austria, an area once inhabited by early Celtic tribes. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

In one cemetery in Hami, in northeastern Xinjiang, archaeologists found plaid fabric similar to what you'd see on a Scottish kilt. Elizabeth Barber, a professor emeritus at Occidental College and a leading expert on ancient textiles, used the cloth to surmise that the mummies shared Celtic ancestry with the Scots. In fact, the cloth was almost the same as samples found in ancient salt mines in Hallstatt, Austria, an area once inhabited by early Celtic tribes. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]2,500-Year-Old Noodles, Cakes and Porridge Found in Xinjiang

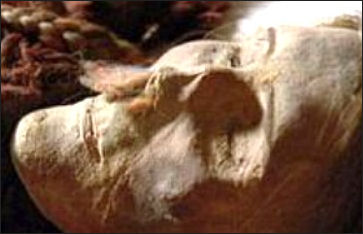

Goldilocks, Tarim mummy

In 2010, Jennifer Viegas wrote in Discovery News, “noodles, cakes, porridge, and meat bones dating to around 2,500 years ago were unearthed at a Chinese cemetery, according to a paper that appeared in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Since the cakes were cooked in an oven-like hearth, the findings suggest that the Chinese may have been among the world's first bakers. Prior research determined the ancient Egyptians were also baking bread at around the same time, but this latest discovery indicates that individuals in northern China were skillful bakers who likely learned baking and other more complex cooking techniques much earlier. [Source: Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News, November 19, 2010]

In 2010, Jennifer Viegas wrote in Discovery News, “noodles, cakes, porridge, and meat bones dating to around 2,500 years ago were unearthed at a Chinese cemetery, according to a paper that appeared in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Since the cakes were cooked in an oven-like hearth, the findings suggest that the Chinese may have been among the world's first bakers. Prior research determined the ancient Egyptians were also baking bread at around the same time, but this latest discovery indicates that individuals in northern China were skillful bakers who likely learned baking and other more complex cooking techniques much earlier. [Source: Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News, November 19, 2010] "With the use of fire and grindstones, large amounts of cereals were consumed and transformed into staple foods," lead author Yiwen Gong and his team wrote in the paper. Gong, a researcher at the Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team dug up the foods at the Subeixi Cemeteries in the arid Turpan region of Xinjiang. "As a result, the climate is so dry that many mummies and plant remains have been well preserved without decaying," according to the scientists, who added that the human remains they unearthed at the site looked more European than Asian. [Ibid]

"With the use of fire and grindstones, large amounts of cereals were consumed and transformed into staple foods," lead author Yiwen Gong and his team wrote in the paper. Gong, a researcher at the Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team dug up the foods at the Subeixi Cemeteries in the arid Turpan region of Xinjiang. "As a result, the climate is so dry that many mummies and plant remains have been well preserved without decaying," according to the scientists, who added that the human remains they unearthed at the site looked more European than Asian. [Ibid] “The individuals may have been living in a semi agricultural, pastoral artists' community, since a pottery workshop was found nearby, and each person was buried with pottery,” Viegas wrote. “The archaeologists also found bows, arrows, saddles, leather chest-protectors, boots, woodenwares, knives, an iron aw, a leather scabbard, and a sweater in the graves. But the scientists focused this particular study on the excavated food, included noodles mounded in an earthenware bowl.” “The noodles were thin, delicate, more than 19.7 inches in length and yellow in color," according to Lu and his colleagues. "They resemble the La-Mian noodle, a traditional Chinese noodle that is made by repeatedly pulling and stretching the dough by hand." [Ibid]

“The individuals may have been living in a semi agricultural, pastoral artists' community, since a pottery workshop was found nearby, and each person was buried with pottery,” Viegas wrote. “The archaeologists also found bows, arrows, saddles, leather chest-protectors, boots, woodenwares, knives, an iron aw, a leather scabbard, and a sweater in the graves. But the scientists focused this particular study on the excavated food, included noodles mounded in an earthenware bowl.” “The noodles were thin, delicate, more than 19.7 inches in length and yellow in color," according to Lu and his colleagues. "They resemble the La-Mian noodle, a traditional Chinese noodle that is made by repeatedly pulling and stretching the dough by hand." [Ibid] The food also included “sheep's heads (which may have held symbolic meaning), another earthenware bowl full of porridge, and elliptical-shaped cakes as well as round baked goods that resembled modern Chinese moon cakes. Chemical analysis of the starches revealed that both the noodles and cakes were made of common millet. The scientists next put new millet through a barrage of cooking experiments to see if they could duplicate the micro-structure of the ancient foods, which would then reveal how the prehistoric chefs cooked the millet. The researchers determined that boiling damages the appearance of individual millet grains, while baking leaves them more intact. The scientists therefore believe the millet grains in one bowl were once boiled into porridge, the noodles were boiled, and the cakes were baked.” [Ibid]

The food also included “sheep's heads (which may have held symbolic meaning), another earthenware bowl full of porridge, and elliptical-shaped cakes as well as round baked goods that resembled modern Chinese moon cakes. Chemical analysis of the starches revealed that both the noodles and cakes were made of common millet. The scientists next put new millet through a barrage of cooking experiments to see if they could duplicate the micro-structure of the ancient foods, which would then reveal how the prehistoric chefs cooked the millet. The researchers determined that boiling damages the appearance of individual millet grains, while baking leaves them more intact. The scientists therefore believe the millet grains in one bowl were once boiled into porridge, the noodles were boiled, and the cakes were baked.” [Ibid] "Baking technology was not a traditional cooking method in the ancient Chinese cuisine, and has been seldom reported to date," according to the authors, who nevertheless believe these latest food discoveries indicate baking must have been a widespread cooking practice in northwest China 2,500 years ago. [Ibid]

"Baking technology was not a traditional cooking method in the ancient Chinese cuisine, and has been seldom reported to date," according to the authors, who nevertheless believe these latest food discoveries indicate baking must have been a widespread cooking practice in northwest China 2,500 years ago. [Ibid] “ The discoveries add to the growing body of evidence that millet was the grain of choice for this part of China. Houyuan Lu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Geology and Physics, along with other researchers, unearthed millet-made noodles dating to 4,000 years ago at the Laija archaeological site, also in northwest China. Gong and his team point out that millet was domesticated about 10,000 years ago in northwest China and was probably a food staple because of its drought resistance and ability to grow in poor soils. [Ibid]

“ The discoveries add to the growing body of evidence that millet was the grain of choice for this part of China. Houyuan Lu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Geology and Physics, along with other researchers, unearthed millet-made noodles dating to 4,000 years ago at the Laija archaeological site, also in northwest China. Gong and his team point out that millet was domesticated about 10,000 years ago in northwest China and was probably a food staple because of its drought resistance and ability to grow in poor soils. [Ibid]Significance of the Mummies from Western China

Tarim mummy

They show that before the arrival of the Han Chinese, Western China was occupied by people with Caucasian features. The ancient cities of Niya and Loulan thrived around the rivers and lakes of Tarim basis in the Taklimakan desert and died out when the water sources dried up. [Source: Thomas B. Allen, National Geographic, March 1996]

They show that before the arrival of the Han Chinese, Western China was occupied by people with Caucasian features. The ancient cities of Niya and Loulan thrived around the rivers and lakes of Tarim basis in the Taklimakan desert and died out when the water sources dried up. [Source: Thomas B. Allen, National Geographic, March 1996] A noticeable number of non-Chinese in western China today have blue eyes and light brown or reddish hair. Uighur nationalists in the western Chinese region of Xinjiang claim that the Loulan Beauty is "the mother of her nation" and use her as proof that local groups like the Uighurs were in Xinjiang long before the Han Chinese. Modern pop song have been written about her and posters with re-creations of her face are used to sell cassettes with the song.

A noticeable number of non-Chinese in western China today have blue eyes and light brown or reddish hair. Uighur nationalists in the western Chinese region of Xinjiang claim that the Loulan Beauty is "the mother of her nation" and use her as proof that local groups like the Uighurs were in Xinjiang long before the Han Chinese. Modern pop song have been written about her and posters with re-creations of her face are used to sell cassettes with the song. The features of the mummies are so striking that some scholars have speculated that the ancient people of Western China could have been relatives of the Celts. The Tarim Basin is near the homeland of the Tocharians, the easternmost speakers of Indo-European languages. Their language was more similar to Celtic and Germanic languages than the Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iran languages spoken by geographically close people. Some scholars believe the people of ancient western China spoke Tocharian. Fifteen-hundred-year-old manuscripts written in Tocharian have been found in the Tarim basin.

The features of the mummies are so striking that some scholars have speculated that the ancient people of Western China could have been relatives of the Celts. The Tarim Basin is near the homeland of the Tocharians, the easternmost speakers of Indo-European languages. Their language was more similar to Celtic and Germanic languages than the Balto-Slavic and Indo-Iran languages spoken by geographically close people. Some scholars believe the people of ancient western China spoke Tocharian. Fifteen-hundred-year-old manuscripts written in Tocharian have been found in the Tarim basin. The diagonal twill weaving pattern of the 4,000-year-old wool clothes of the mummies is remarkably similar to the weaving of the ancient Celts. In her book, The Mummies of Urumchi, Elizabeth Wayland Barber argues the similarities are too unique to be a coincidence and this means contact between Central Asia and Europe was much earlier than previously thought.

The diagonal twill weaving pattern of the 4,000-year-old wool clothes of the mummies is remarkably similar to the weaving of the ancient Celts. In her book, The Mummies of Urumchi, Elizabeth Wayland Barber argues the similarities are too unique to be a coincidence and this means contact between Central Asia and Europe was much earlier than previously thought.Evidence Tarim Mummies Came from the West

The theory that the earliest mummies came from the west is supported by a number of scholars. Textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber wrote in her book The Mummies of Urumchi that the kind of cloth discovered in the oldest grave sites can be traced to the Caucasus. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008]

The theory that the earliest mummies came from the west is supported by a number of scholars. Textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber wrote in her book The Mummies of Urumchi that the kind of cloth discovered in the oldest grave sites can be traced to the Caucasus. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008] Han Kangxin, a physical anthropologist, has also concluded that the earliest settlers were not Asians. He has studied the skulls of the mummies, and says that genetic tests can be unreliable. It’s very clear that these are of Europoid or Caucasoid origins. Of the hundreds of mummies discovered, there are some that are East Asian, but they are not as ancient as the Loulan Beauty or the Cherchen Man. The most prominent Chinese grave sites were discovered at a place called Astana, believed to be a former military outpost. The findings at the site span the Jin to the Han dynasties, from the third to the 10th centuries. “ [Ibid]

Han Kangxin, a physical anthropologist, has also concluded that the earliest settlers were not Asians. He has studied the skulls of the mummies, and says that genetic tests can be unreliable. It’s very clear that these are of Europoid or Caucasoid origins. Of the hundreds of mummies discovered, there are some that are East Asian, but they are not as ancient as the Loulan Beauty or the Cherchen Man. The most prominent Chinese grave sites were discovered at a place called Astana, believed to be a former military outpost. The findings at the site span the Jin to the Han dynasties, from the third to the 10th centuries. “ [Ibid]Politically-Tinged Study of the Tarim Mummies

Tarim mummy

Edward Wong of New York Times wrote, ‘Some foreign scholars say the Chinese government, eager to assert anarrative of longtime Chinese dominance of Xinjiang, is unwilling to face the fact that the mummies provide evidence of heterogeneity throughout the region’s history of human settlement. As a result, they say, the government has been unwilling to give broad access to foreign scientists to conduct genetic tests on the mummies.’ [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008]

Edward Wong of New York Times wrote, ‘Some foreign scholars say the Chinese government, eager to assert anarrative of longtime Chinese dominance of Xinjiang, is unwilling to face the fact that the mummies provide evidence of heterogeneity throughout the region’s history of human settlement. As a result, they say, the government has been unwilling to give broad access to foreign scientists to conduct genetic tests on the mummies.’ [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008] “In terms of advanced scientific research on the mummies, it’s just not happening, said Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania who has been at the forefront of foreign scholarship of the mummies. Mair first spotted one of the mummies, a red-haired corpse called the Cherchen Man, in the back room of a museum in Urumqi while leading a tour of Americans there in 1988, the first year the mummies were put on display.” [Ibid]

“In terms of advanced scientific research on the mummies, it’s just not happening, said Victor H. Mair, a professor of Chinese language and literature at the University of Pennsylvania who has been at the forefront of foreign scholarship of the mummies. Mair first spotted one of the mummies, a red-haired corpse called the Cherchen Man, in the back room of a museum in Urumqi while leading a tour of Americans there in 1988, the first year the mummies were put on display.” [Ibid] “Since then, he says that he has been obsessed with pinpointing the origins of the mummies, intent on proving a theory dear to him: that the movement of peoples throughout history is far more common than previously thought. Mair has assembled various groups of scholars to do research on the mummies. In 1993, the Chinese government tried to prevent Mair from leaving China with 52 tissue samples after having authorized him to go to Xinjiang and to collect them. But a Chinese researcher managed to slip a half-dozen vials to Mair. From those samples, an Italian geneticist concluded in 1995 that at least two of the mummies had a European genetic marker.” [Ibid]

“Since then, he says that he has been obsessed with pinpointing the origins of the mummies, intent on proving a theory dear to him: that the movement of peoples throughout history is far more common than previously thought. Mair has assembled various groups of scholars to do research on the mummies. In 1993, the Chinese government tried to prevent Mair from leaving China with 52 tissue samples after having authorized him to go to Xinjiang and to collect them. But a Chinese researcher managed to slip a half-dozen vials to Mair. From those samples, an Italian geneticist concluded in 1995 that at least two of the mummies had a European genetic marker.” [Ibid] “The Chinese government in recent years has allowed genetic research on the mummies to be conducted only by Chinese scientists. Jin Li, a well-known geneticist at Fudan University in Shanghai, tested the mummies in conjunction with a 2007 National Geographic documentary. He concluded that some of the oldest mummies had East Asian and even South Asian markers, though the documentary said further testing needed to be done. Mair has disputed any suggestion that the mummies were from East Asia. He believes that East Asian migrants did not appear in the Tarim Basin until much later than the Loulan Beauty and her people.” [Ibid]

“The Chinese government in recent years has allowed genetic research on the mummies to be conducted only by Chinese scientists. Jin Li, a well-known geneticist at Fudan University in Shanghai, tested the mummies in conjunction with a 2007 National Geographic documentary. He concluded that some of the oldest mummies had East Asian and even South Asian markers, though the documentary said further testing needed to be done. Mair has disputed any suggestion that the mummies were from East Asia. He believes that East Asian migrants did not appear in the Tarim Basin until much later than the Loulan Beauty and her people.” [Ibid]Tarim Mummies and Uighur Nationalism

Yingpan Man

The Tarim mummies seem to indicate that the very first people to settle Xinjiang came from the west not the Chinese interior. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, ‘Uighur nationalists have gleaned evidence from the mummies, whose corpses span thousands of years, to support historical claims to the region. Foreign scholars say that at the very least, the Tarim mummies show that Xinjiang has always been a melting pot, a place where people from various corners of Eurasia founded societies and where cultures overlapped. Contact between peoples was particularly frequent in the heyday of the Silk Road, when camel caravans transported goods that flowed from as far away as the Mediterranean. It’s historically been a place where cultures have mixed together, said Yidilisi Abuduresula, 58, a Uighur archaeologist in Xinjiang working on the mummies.’ [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008]

The Tarim mummies seem to indicate that the very first people to settle Xinjiang came from the west not the Chinese interior. Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, ‘Uighur nationalists have gleaned evidence from the mummies, whose corpses span thousands of years, to support historical claims to the region. Foreign scholars say that at the very least, the Tarim mummies show that Xinjiang has always been a melting pot, a place where people from various corners of Eurasia founded societies and where cultures overlapped. Contact between peoples was particularly frequent in the heyday of the Silk Road, when camel caravans transported goods that flowed from as far away as the Mediterranean. It’s historically been a place where cultures have mixed together, said Yidilisi Abuduresula, 58, a Uighur archaeologist in Xinjiang working on the mummies.’ [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, November 18, 2008] ‘Some Uighurs have latched on to the fact that the oldest mummies are most likely from the west as evidence that Xinjiang has belonged to the Uighurs throughout history. A modern, nationalistic pop song praising the Loulan Beauty has even become popular. The people found in Loulan were Uighur people, according to the materials,said a Uighur tour guide in the city of Kashgar who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of running afoul of the Chinese authorities.’

‘Some Uighurs have latched on to the fact that the oldest mummies are most likely from the west as evidence that Xinjiang has belonged to the Uighurs throughout history. A modern, nationalistic pop song praising the Loulan Beauty has even become popular. The people found in Loulan were Uighur people, according to the materials,said a Uighur tour guide in the city of Kashgar who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of running afoul of the Chinese authorities.’ “Scholars generally agree that Uighurs did not migrate to what is now Xinjiang from Central Asia until the 10th century. But, uncomfortably for the Chinese authorities, evidence from the mummies also offers a far more nuanced history of settlement than the official Chinese version. By that official account, Zhang Qian, a general of the Han dynasty, led a military expedition to Xinjiang in the second century B.C. His presence isoften cited by the ethnic Han Chinese when making historical claims to the region.

“Scholars generally agree that Uighurs did not migrate to what is now Xinjiang from Central Asia until the 10th century. But, uncomfortably for the Chinese authorities, evidence from the mummies also offers a far more nuanced history of settlement than the official Chinese version. By that official account, Zhang Qian, a general of the Han dynasty, led a military expedition to Xinjiang in the second century B.C. His presence isoften cited by the ethnic Han Chinese when making historical claims to the region.Political Implications of the Xinjiang Mummies

The Xinjiang mummies have added another bone of contention to the raging ethnic conflict in Xinjiang, where Uighurs, a Turkic speaking people, consider themselves to be the indigenous population and the Han Chinese foreign invaders from the east. For years, the Chinese government tried to thwart foreign scholars from looking too deeply into the mummies' origins. In 1993, the government confiscated tissue samples from Xinjiang mummies that Mair and an Italian geneticist, Paolo Francalacci, had collected with permission. (A Chinese scientist, whom Mair declines to name, later slipped the samples into their hands as they were preparing to leave.) Although DNA testing was not as advanced as it is today, the scientists were able to trace a genetic link to Europe. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

The Xinjiang mummies have added another bone of contention to the raging ethnic conflict in Xinjiang, where Uighurs, a Turkic speaking people, consider themselves to be the indigenous population and the Han Chinese foreign invaders from the east. For years, the Chinese government tried to thwart foreign scholars from looking too deeply into the mummies' origins. In 1993, the government confiscated tissue samples from Xinjiang mummies that Mair and an Italian geneticist, Paolo Francalacci, had collected with permission. (A Chinese scientist, whom Mair declines to name, later slipped the samples into their hands as they were preparing to leave.) Although DNA testing was not as advanced as it is today, the scientists were able to trace a genetic link to Europe. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]DNA Testing of the Xinjiang Mummies

In comprehensive study published in February 2010 based on genetic tests of remains from a nearby archeological site — Xiaohe ("Small River"), which lies about 100 miles west of Loulan. Geneticists from China's Jilin and Fudan universities concluded that the ancestors of these ancient people had indeed come from Europe, possibly by way of Siberia. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010]

In comprehensive study published in February 2010 based on genetic tests of remains from a nearby archeological site — Xiaohe ("Small River"), which lies about 100 miles west of Loulan. Geneticists from China's Jilin and Fudan universities concluded that the ancestors of these ancient people had indeed come from Europe, possibly by way of Siberia. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2010] Not only were the mummies not Chinese, but they weren't Uighur either — although their descendants might have eventually been assimilated into the Uighur population, according to Mair, who consulted on that study. "We deflated that bubble,'' he said.

Not only were the mummies not Chinese, but they weren't Uighur either — although their descendants might have eventually been assimilated into the Uighur population, according to Mair, who consulted on that study. "We deflated that bubble,'' he said. The result is that the mummies have shed some of their political sensitivity, allowing them to come out of the closet of China's ethnic troubles. For the first time this year, two mummies traveled to the United States as part of an exhibit titled "Secrets of the Silk Road: Mystery Mummies of China" at Santa Ana's Bowers Museum.

The result is that the mummies have shed some of their political sensitivity, allowing them to come out of the closet of China's ethnic troubles. For the first time this year, two mummies traveled to the United States as part of an exhibit titled "Secrets of the Silk Road: Mystery Mummies of China" at Santa Ana's Bowers Museum. The mummies are also star attractions within China, the centerpiece of the recently refurbished museum in Urumqi, and another in the oasis town of Turpan, 140 miles from Urumqi, where ethnic Chinese mummies discovered in the region are on display.

The mummies are also star attractions within China, the centerpiece of the recently refurbished museum in Urumqi, and another in the oasis town of Turpan, 140 miles from Urumqi, where ethnic Chinese mummies discovered in the region are on display.Early Horsemen

Archaeologists working in Outer Mongolia and Inner Mongolia in China have uncovered the remains of more than 100 walled towns and cities of settled people dating back as far as the 3rd millennium B.C. and found extraordinarily beautiful artifacts such as stone altars and jade dragons. Scattered around Outer Mongolia are burial stones organized in squares and circles. Some cover slab-lined tombs and are thought to date as far back as to 2000 B.C.

Archaeologists working in Outer Mongolia and Inner Mongolia in China have uncovered the remains of more than 100 walled towns and cities of settled people dating back as far as the 3rd millennium B.C. and found extraordinarily beautiful artifacts such as stone altars and jade dragons. Scattered around Outer Mongolia are burial stones organized in squares and circles. Some cover slab-lined tombs and are thought to date as far back as to 2000 B.C. Around 1500 B.C., Mongolia became colder and drier—a climate more conducive to grasslands than crops—prompting a shift from a crop-based to livestock-centered society. Cattle was raised in areas where pastures were rich. Sheep were raised in areas where the pastures were sparser.

Around 1500 B.C., Mongolia became colder and drier—a climate more conducive to grasslands than crops—prompting a shift from a crop-based to livestock-centered society. Cattle was raised in areas where pastures were rich. Sheep were raised in areas where the pastures were sparser. In 1995, perfectly preserved mummified remains of a Scythian nomad and his horse were unearthed from the Ukok Plateau in Siberia near where China, Mongolia and Russia all met. The 3,000-year horseman wore braids, embroidered trousers, a fur coat, high boots. A large elk was tattooed across his back and chest.

In 1995, perfectly preserved mummified remains of a Scythian nomad and his horse were unearthed from the Ukok Plateau in Siberia near where China, Mongolia and Russia all met. The 3,000-year horseman wore braids, embroidered trousers, a fur coat, high boots. A large elk was tattooed across his back and chest. The Scythians were Indo-Iranian horse people who migrated from Central Asia near China to the European Steppe north of the Black Sea around 700 B.C. For 400 years they dominated an area that stretched from the Danube across the Ukraine, Crimea and southern Russia to the Don River and the Ural Mountains and then mysteriously vanished. The Scythians preceded the Huns, Turks and Mongols by many centuries. The were not a unified group but rather a confederation of related, warring nomadic tribes. It is believed that they spoke an Indo-European language similar to Persian.

The Scythians were Indo-Iranian horse people who migrated from Central Asia near China to the European Steppe north of the Black Sea around 700 B.C. For 400 years they dominated an area that stretched from the Danube across the Ukraine, Crimea and southern Russia to the Don River and the Ural Mountains and then mysteriously vanished. The Scythians preceded the Huns, Turks and Mongols by many centuries. The were not a unified group but rather a confederation of related, warring nomadic tribes. It is believed that they spoke an Indo-European language similar to Persian. Uighurs arrived in the 10th century. See Uighurs

Uighurs arrived in the 10th century. See UighursChina and Xinjiang

China maintains that Xinjiang has been an integral part of China since 60 B.C. and that it is has maintained control of the region with the exception of a few brief periods. Muslims in Xinjiang refute this claim. The Chinese say they established military garrisons in what is now Xinjiang as early as 200 B.C. and say the region came under Chinese control briefly during the Han dynasty in A.D. 50. China returned to again during the Tang dynasty (618-907) but withdrew after the dynasty collapsed. Xinjiang was part of the Mongol-Yuan empire which also encompassed China. The oldest evidence of Chinese presence are some graves at a place called Astana, believed to have been a military garrison that existed there sometime between the A.D. 3rd and the 10th century

China maintains that Xinjiang has been an integral part of China since 60 B.C. and that it is has maintained control of the region with the exception of a few brief periods. Muslims in Xinjiang refute this claim. The Chinese say they established military garrisons in what is now Xinjiang as early as 200 B.C. and say the region came under Chinese control briefly during the Han dynasty in A.D. 50. China returned to again during the Tang dynasty (618-907) but withdrew after the dynasty collapsed. Xinjiang was part of the Mongol-Yuan empire which also encompassed China. The oldest evidence of Chinese presence are some graves at a place called Astana, believed to have been a military garrison that existed there sometime between the A.D. 3rd and the 10th century The Chinese periodically sent in the military to claim Xinjiang, with the soldiers followed by farmers and workers building irrigation works. In Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland James A. Millward and Peter C. Perdue wrote: “By first establishing military and civil administrations and then promoting immigration and agricultural settlements, it went far towards assuring the continued presence of China-based power in the region.”

The Chinese periodically sent in the military to claim Xinjiang, with the soldiers followed by farmers and workers building irrigation works. In Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland James A. Millward and Peter C. Perdue wrote: “By first establishing military and civil administrations and then promoting immigration and agricultural settlements, it went far towards assuring the continued presence of China-based power in the region.” Xinjiang was largely independent of China during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), a fact that China does not acknowledge in its modern history books, and remained that way until 1759. During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), China returned to Xinjiang because of its strategic location and resources.

Xinjiang was largely independent of China during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), a fact that China does not acknowledge in its modern history books, and remained that way until 1759. During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), China returned to Xinjiang because of its strategic location and resources. In the 18th century the Emperor Qianlong launched a campaign to claim Xinjiang after effort to rule it through Mongolian and Uighur proxies failed. His campaign went far beyond anything that occurred before. More than 50,000 troops were demobilized and offered benefits if they stayed and farmed. Free land and seeds were given to Chinese who migrated there.

In the 18th century the Emperor Qianlong launched a campaign to claim Xinjiang after effort to rule it through Mongolian and Uighur proxies failed. His campaign went far beyond anything that occurred before. More than 50,000 troops were demobilized and offered benefits if they stayed and farmed. Free land and seeds were given to Chinese who migrated there. Conquests by China in the 18th century in western and southern China nearly doubled the country's size. The Chinese did not exert much control over Xinjiang until the 19th century. Even then Chinese hold on the region was tenuous. Frequent rebellions prevented the Chinese from solidifying their control of the region until mid 20th century. Xinjiang wasn't incorporated into China until 1955, six years after the People's Republic was created.

Conquests by China in the 18th century in western and southern China nearly doubled the country's size. The Chinese did not exert much control over Xinjiang until the 19th century. Even then Chinese hold on the region was tenuous. Frequent rebellions prevented the Chinese from solidifying their control of the region until mid 20th century. Xinjiang wasn't incorporated into China until 1955, six years after the People's Republic was created.Xinjiang and the Silk Road

Many Silk Road caravans traveled through Xinjiang. Traders traveling between the Middle East, Europe and western China traveled through the passes between Xinjiang and Central Asia. Traders traveled between India and western China traveled on Himalayan caravan routes over Karakoram Pass between Kashgar in Xinjiang and the Gilgit and Hunza valleys in present Pakistan.

Many Silk Road caravans traveled through Xinjiang. Traders traveling between the Middle East, Europe and western China traveled through the passes between Xinjiang and Central Asia. Traders traveled between India and western China traveled on Himalayan caravan routes over Karakoram Pass between Kashgar in Xinjiang and the Gilgit and Hunza valleys in present Pakistan. Describing Kashgar Marco Polo wrote: "The people are for the most part idolaters, but there are also some Nestorian Christians and Saracens...the inhabitants live by trade and industry. They have fine orchards and vineyards and flourishing estates. Cotton grows here in plenty, besides flax and hemp. The soil is fertile and productive of all the means of life. The country is the starting point from which many merchants set out to market their wares all over the world."

Describing Kashgar Marco Polo wrote: "The people are for the most part idolaters, but there are also some Nestorian Christians and Saracens...the inhabitants live by trade and industry. They have fine orchards and vineyards and flourishing estates. Cotton grows here in plenty, besides flax and hemp. The soil is fertile and productive of all the means of life. The country is the starting point from which many merchants set out to market their wares all over the world."Early Silk Road Explorers

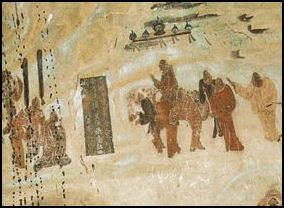

Zhang Qian in a 7th century

Dunhuanshang mural

More than 1,300 years before Marco Polo left Italy for China on the Silk Road, Chinese explorers were traveling nearly as far to reach Central Asia and the Middle East. In 138 B.C., the Chinese explorer Chang Chien (Zang Qian) was sent westward by Emperor Wu (140-87 B.C.) with the assignment of finding allies to fight the Xiongnu. He was captured by the Xiongnu soon after departing and was held in captivity for 10 years before he escaped and crossed the Pamir mountains to reach the Fergana Valley

More than 1,300 years before Marco Polo left Italy for China on the Silk Road, Chinese explorers were traveling nearly as far to reach Central Asia and the Middle East. In 138 B.C., the Chinese explorer Chang Chien (Zang Qian) was sent westward by Emperor Wu (140-87 B.C.) with the assignment of finding allies to fight the Xiongnu. He was captured by the Xiongnu soon after departing and was held in captivity for 10 years before he escaped and crossed the Pamir mountains to reach the Fergana Valley Chang Chien reached Syria, and possibly Egypt, and returned to China 19 years after he set out and long after the Xiongnu were subdued. In the first great account of Silk Road travel he described the pleasures of Central Asian wine and fantastic animals such as the "heavenly horses" of the Fergana Valley that had striped bodies and sweated blood.

Chang Chien reached Syria, and possibly Egypt, and returned to China 19 years after he set out and long after the Xiongnu were subdued. In the first great account of Silk Road travel he described the pleasures of Central Asian wine and fantastic animals such as the "heavenly horses" of the Fergana Valley that had striped bodies and sweated blood. The Chinese monk Fa-hsien left China around A.D. 399 to study Buddhism and locate sutras and relics in India. He traveled from Xian to the west overland on the southern Silk Road into Central Asia and described monasteries, monks and pagodas. He crossed over Himalayan passes into India and ventured as far south as Sri Lanka before sailing back to China on a route that took him through present-day Indonesia. His entire journey took 15 years.

The Chinese monk Fa-hsien left China around A.D. 399 to study Buddhism and locate sutras and relics in India. He traveled from Xian to the west overland on the southern Silk Road into Central Asia and described monasteries, monks and pagodas. He crossed over Himalayan passes into India and ventured as far south as Sri Lanka before sailing back to China on a route that took him through present-day Indonesia. His entire journey took 15 years.Xuanzang

In A.D. 645, the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hsuan-tsang) left China for India to obtain Buddhist texts from which the Chinese could learn more about Buddhism. He made it to Central Asia and India despite being held up by surly Chinese guards and guides who abandoned him in the middle of nowhere. In Central Asia he traveled to Turfan, Kucha, the Bedel pass, Lake Issyk-kul, the Chu Valley (near present-day Bishkek), Tashkent, Samarkand, Balk, Kashgar and Khoton before crossing the Himalayas into India.

In A.D. 645, the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Hsuan-tsang) left China for India to obtain Buddhist texts from which the Chinese could learn more about Buddhism. He made it to Central Asia and India despite being held up by surly Chinese guards and guides who abandoned him in the middle of nowhere. In Central Asia he traveled to Turfan, Kucha, the Bedel pass, Lake Issyk-kul, the Chu Valley (near present-day Bishkek), Tashkent, Samarkand, Balk, Kashgar and Khoton before crossing the Himalayas into India. Xuanzang spent 16 years in India collecting texts and returned with 700 Buddhist texts. His journey inspired the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West by Wu Ch'eng-en, a story about a wanderings Buddhist monk accompanied by a pig, an immortal that poses as a monkey and a feminine spirit.

Xuanzang spent 16 years in India collecting texts and returned with 700 Buddhist texts. His journey inspired the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West by Wu Ch'eng-en, a story about a wanderings Buddhist monk accompanied by a pig, an immortal that poses as a monkey and a feminine spirit.

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The human skeletons were piled up like signposts in the sand. For Xuanzang, a Buddhist monk traveling the Silk Road in A.D. 629, the bleached-out bones were reminders of the dangers that stalked the world's most vital thoroughfare for commerce, conquest, and ideas. Swirling sandstorms in the desert beyond the western edge of the Chinese Empire had left the monk disoriented and on the verge of collapse. Rising heat played tricks on his eyes, torturing him with visions of menacing armies on distant dunes. More terrifying still were the sword-wielding bandits who preyed on caravans and their cargo—silk, tea, and ceramics heading west to the courts of Persia and the Mediterranean, and gold, gems, and horses moving east to the Tang dynasty capital of Changan, among the largest cities in the world. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010]

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The human skeletons were piled up like signposts in the sand. For Xuanzang, a Buddhist monk traveling the Silk Road in A.D. 629, the bleached-out bones were reminders of the dangers that stalked the world's most vital thoroughfare for commerce, conquest, and ideas. Swirling sandstorms in the desert beyond the western edge of the Chinese Empire had left the monk disoriented and on the verge of collapse. Rising heat played tricks on his eyes, torturing him with visions of menacing armies on distant dunes. More terrifying still were the sword-wielding bandits who preyed on caravans and their cargo—silk, tea, and ceramics heading west to the courts of Persia and the Mediterranean, and gold, gems, and horses moving east to the Tang dynasty capital of Changan, among the largest cities in the world. [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, June 2010] What kept Xuanzang going, he wrote in his famous account of the journey, was another precious item carried along the Silk Road: Buddhism itself. Other religions surged along this same route—Manichaeism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and later, Islam—but none influenced China so deeply as Buddhism, whose migration from India began sometime in the first three centuries A.D. The Buddhist texts Xuanzang carted back from India and spent the next two decades studying and translating would serve as the foundation of Chinese Buddhism and fuel the religion's expansion.

What kept Xuanzang going, he wrote in his famous account of the journey, was another precious item carried along the Silk Road: Buddhism itself. Other religions surged along this same route—Manichaeism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and later, Islam—but none influenced China so deeply as Buddhism, whose migration from India began sometime in the first three centuries A.D. The Buddhist texts Xuanzang carted back from India and spent the next two decades studying and translating would serve as the foundation of Chinese Buddhism and fuel the religion's expansion. Near the end of his 16-year journey, the monk stopped in Dunhuang, a thriving Silk Road oasis where crosscurrents of people and cultures were giving rise to one of the great marvels of the Buddhist world, the Mogao caves.

Near the end of his 16-year journey, the monk stopped in Dunhuang, a thriving Silk Road oasis where crosscurrents of people and cultures were giving rise to one of the great marvels of the Buddhist world, the Mogao caves.Image Sources: Uighur images website; Silk Road Foundation; Wikipedia; Shanghai Museum; British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento